1st Place Winner

Via Boito

By Mitchell Lee Edwards

Mitchell Lee Edwards, "Via Boito" Ensign, March 1981, 39

The train was crowded, so I stood by the door and gazed out the window. It was hot, and the scorched Apennine Mountains seemed dry, brown, and uninteresting. "You'll love the Appenines," said a man selling oranges at the station. Impressive or not, they weren't foremost on my mind. I was a new zone leader, and I wanted to baptize.

The Florence station was large, and I had to stop several times to rest my arms before arriving at the taxis with my two years' supply of white shirts, ties, and books. A big, smiling taxi-driver shouted, "Vieni qui ragazzo!" I staggered towards him and dropped my bulging cases in front of his car. "Via," I gasped, "Boito."

Friendly and outgoing, he pointed to several landmarks as we worked our way through winding streets to Via Boito -- my new apartment. I didn't pay much attention to him -- my mind was on zone conferences and zone visits and interviews.

Elder Lewis was standing out in front when I pulled up. Tall, blond, and sun-tanned, he stared at me as I fumbled through my pockets in a frantic search for lira. A teacher had told me in high school that first impressions often determine success. There I was, a new zone leader, and I couldn't even remember where I had put my money. Feeling like a failure, I finally asked Elder Lewis if he had 1,500 lira.

Fare paid, we carried my suitcases up the stairs to our second-floor apartment.

As I had hung up the phone a day earlier, I had thought to myself, "Me? A zone leader? They can't do this to me. I'm already tired of trying to be a perfect missionary, and now I'll have to push for statistics and numbers and enthusiasm even more."

I had in my mind a picture of what I thought I was "supposed to do," and I was determined to do just that. Early in my mission I had decided that the only reason for being in the mission field is to baptize. So now there was one major goal in my head: to "psyche" the zone into baptizing as many people as we possibly could. It was my goal -- one that I thought a young fireball zone leader should have.

"What was Reggio Emilia like?" Elder Lewis asked as I hung up my ties.

"Great!" I blurted out. "We were teaching twenty discussions a week, selling ten copies of the Book of Mormon, and putting in eighty hours." I thought it sounded impressive.

"E beh," Lewis replied, which means, loosely translated, "Do you want a trophy or something?"

I couldn't figure out why he wasn't excited about my statistics -- goodness knows he couldn't have been doing much better. At least it didn't seem possible. But, then, maybe zone leaders were everything I thought they were. Maybe they really did teach thirty lessons every week and stay out of the apartment for one hundred hours. Would I have to start working that hard? Not wanting to pursue the thought, I went to see what was on the stove for lunch.

There were two other elders living in the apartment with us; we talked for a while during lunch, but the conversation began to drag after a few minutes. Trying to pep it up with a little enthusiastic baptism talk, I gushed to the other two, "Elder Lewis and I challenge you to a baptismal contest this month." Silence. "Whichever companionship baptizes the most eats the pizzas of their choice at the other's expense. Do you feel up to it?"

Another painful moment of silence. Then, "Yeah, I guess so."

"Well, Elder Lewis, we'd better get out there early in the morning tomorrow, because I l-o-o-ve pizza." I looked to Elder Lewis for some supportive comment; but he was busy grating Parmigiano cheese over his spaghetti. I looked around for a hole to crawl into.

Something was wrong. I was doing my best to be a fireball, baptism-conscious zone leader, but it wasn't working. Maybe I just wasn't trying hard enough, I concluded.

After district meeting Elder Lewis suggested that we visit Brother Bilotta, first counselor in the branch presidency. "He usually gives us something to eat and occasionally makes us stay and eat a full dinner with him." I interjected, "Maybe we can ask him for the names of all his friends, so that we can start teaching them." Elder Lewis remained silent.

The evening progressed, but an opportunity to ask Brother Bilotta for his friends' names never materialized. True to form, he offered us something to eat, and then insisted that we stay for supper. It was great fun; we laughed a lot, looked at pictures of the Bilotta family vacations to Sicily, and ate almost a kilo of Italian "bel paese" cheese. It was late when we arrived at our apartment, exhausted but wonderfully full. We knelt and prayed for more baptisms in the zone and for our families and girlfriends, then climbed between those itchy Italian sheets. I had completed one day as a zone leader.

"We were called here to be successful," I said in my talk at a zone conference a week later, "and that means teaching fifteen lessons, selling ten copies of the Book of Mormon, and working eighty hours every single week!" Though Elder Lewis and I hadn't even come close to doing that the previous week, I nevertheless thought it a good challenge. The missionaries seemed rather excited about it, so I felt good about my presentation. I had said just about what I thought a zone leader should say, and I was content. For a season.

As we drove home from Brother Bilotta's house that evening, I tried to get up courage to tell Elder Lewis that I thought we should be working more. "Do you think zone leaders should be examples for the rest of the missionaries in their zone?" I ventured.

"Yeah, I think so," he replied.

I took a deep breath, and said, "Do you think we're being good examples?"

"Yeah, I think so."

"Well, I don't."

The sound of the tires on the cobblestones muffled the few words he mumbled. I stared out the side window and silently prayed for the ability to say what I really had in mind. I tried several times, but the words wouldn't form into a coherent sentence.

"Elder Lewis," I finally blurted out, "I don't think we're teaching enough lessons or putting in enough hours to warrant going to Brother Bilotta's house every other night. We're the zone leaders here, and I think we should have the best report forms in the entire zone. At this rate, we'll have the worst." We arrived at the Arno and turned left, giving me an unobstructed view of the wide, dark river. He broke the silence.

"Elder Edwards, I don't really care about your report form. I may not be entirely right in going to Brother Bilotta's house when there's nothing else to do -- I'll admit that. I'll even admit that I'm not working as hard as I probably should be. It's probably a bad attitude. But you're not blameless yourself. You live for that report form. Your life is determined by the numbers that show up there each week. You really don't care if you've helped someone, or if you've grown to love someone, or if you've developed a love and respect for this people and this country. As long as you have your numbers on your report, as long as you impress others with your 'baptism enthusiasm,' as long as you're 'Joe zone leader,' you're happy. You're cold, and you're statistical. And I don't think that's right, either."

Silence. I looked out at the fog as we drove along the Arno river, and slowly and deliberately thought to myself, "He's right."

I didn't sleep well that night, but it was perhaps the most significant night of my mission. My mind raced backward. "You've got to love the people," my bishop at home had told me. It made sense to me at that time, and I wrote it down in my journal. How could I effectively work with the Italian people for two years if I didn't have a strong love for them and a respect for their way of life? My older brother had said to me at the airport, "You think it's hard to leave America? Wait until you try to leave Italy after working there for two years and developing a love that will never die. One of the greatest treasures of your mission will be the love that you'll develop for Italy and Italians."

And Dad had once said to me, "Mitch, you'll be amazed at the bonds of love that you'll develop with people over there. You'll praise Italy and Italians the rest of your life. You'll feel sort of like an 'adopted Italian,' and you'll carry with you the rest of your life a desire to return to Italy."

As I lay there in my Via Boito itchy sheets, it all hit me like a brick wall. I did not love Italy. It was a nice place and all, but I often found myself passing judgment: Everything was decidedly old and run down and archaic. Too many carbohydrates in the food, too hot and humid during the summer. Too many apartment buildings in the cities, lousy roads in the country. Everything was too small and too old and too cramped.

And toward Italians, my sentiments were occasionally anything but loving. After a bad day, I often succumbed to my own biases: Too heavy. Unschooled. Too casual. Steeped in tradition, and living in the past. Too emotional and outspoken. My mental list started to frighten me as I looked at it with new perspective.

Where, and why, had I gone wrong? I was only trying to do my best, and I thought that teaching a lot of discussions was a good measure of success. I'd decided early in my mission that good missionaries have good report forms every week. I wanted to be a good missionary, so I became an expert at getting good report forms.

My desire to teach and work hard was not bad -- on the contrary, it was honorable and desirable. But I was missing something very important-and until Elder Lewis mentioned it on the way home from Brother Bilotta's, it had never occurred to me. I had failed to even try to love, understand, or appreciate Italy and its people.

As Elder Lewis and I were tracting several days later, the Roman walls on both sides of the small cobblestone mountain road caught my attention in a way they never had before. "Just a sec, Elder Lewis. Can we stop here for a minute or two?"

"Why?"

He cracked a little smile as I said, "I just want to look at this wall for a moment."

We sat down on the cobblestones and watched the wall in silence. I traced the chisel marks of a Roman stonecutter, examined the mortar that had tenaciously held those stones together century after century, noticed the oxidizing stub of what was probably a lantern support, and eyed the Italian ant that crawled upon it, oblivious to the wall's history and obvious cultural significance. After a minute I said, "OK, I'm finished. let's go on."

As we made our way down a narrow, dimly lit, winding road late one evening after tracting, we passed by a small fruit stand tucked away in a little opening in the stone wall. Beside it sat an old man, probably in his eighties, bent over and looking at his worn shoes. He slowly raised his head and looked at us with tired eyes as we walked by. I paused, tapped Elder Lewis on the shoulder, and we returned to the old man.

"How much is a carrot?"

In a weak, humble voice, he slowly replied, "Centro lire."

"Give me the biggest one you have."

As his crooked hands searched through the box for a large carrot, I searched my pockets for a hundred lira piece. I had nothing but a thousand lira bill, and was about to tell him to forget it, when I noticed his face. Tired and rough and wrinkled, his face nevertheless seemed to emanate a warmness -- a sort of light. I finally decided it was his eyes -- they fairly glowed with that cheerful warmth. An Italian warmth. He handed me a large fat carrot, and I handed him the thousand lira.

He slowly looked at the bill, and then apologized, "Mi displace, non ho cambio. Mangia la carota," and tried to give the money back to me.

"No," I said, "go ahead and keep it. It's now yours."

He thought I didn't understand the price, but I insisted, "You've worked hard today- keep the change and buy yourself a fruitcake. They bake good ones down on the corner."

When he finally understood, the most innocent, genuine smile I've ever seen broke out on his face, and tears came to his eyes. Calling us angels, he kissed our cheeks before we slipped away.

"Did you see his face?" I whispered several minutes later. "Did you see that look in his eyes? It was so..." I struggled for an adjective. Warm, beautiful genuine -- all ran through my mind, but they didn't fit. "It was so...," and then the word came. It was perfect. It was so Italian.

Elder Lewis and I began to find deepening satisfaction in working with Italians, and we became near "workaholics" as a result. Our desire to be with the people became almost overwhelming. I would see an old man, probably a shoemaker, walking home with a big loaf of fresh Italian bread, and I couldn't hold myself from running up to him and talking. The smell of fish in the open market, once repulsive to me, began to stir my sentiments. I was slowly falling in love with the people, the country, and the Italian way of life.

Instead of returning to our apartment for lunch, we'd duck into an alimentari and buy a hunk of cheese, a loaf of hard, chewy bread, and a clump of grapes, and sit in Piazza della Signoria or on the banks of the Arno or on Ponte Vecchio or just on some "Italian looking street," and talk with Italians as we consumed our "gourmet" lunch. In testimony meeting one Sunday, I found myself saying to the branch of Italian Saints, "Something is happening to me, and . . . well . . . I'm not quite sure what it is. I'm starting to feel like I belong here; like my name should be Eduardo instead of Edwards. I guess... well... I love you all."

I began to notice that Italians did things differently than we Americans do them, and it fascinated me. Italians buy bread and vegetables daily, and always in the morning. It used to anger me that no one would ever be home in the mornings. But understanding them, we'd go to the bakeries and the open-air fruit markets and plunge right in to talk with the people as they did their shopping. They'd listen to us, and they'd invite us into their homes. We began to teach more. Our greatest joy was going to the markets and the docks, presenting our message to the Italians in their language, "on their turf."

We were welcomed into more homes, talked with more people, taught more lessons, and were happier than ever. It was a miracle, and the counsel of my loved ones at home became my creed: love the country, love the people. Only then will miracles happen.

Like the miracle that happened with one of our investigators, Pasquale. Pasquale wept as we spoke of the reunion with our loved ones after this life. God speaking through prophets again to man seemed perfectly logical to him. He even bought two large pots and planted tomatoes on his apartment balcony after reading a speech by President Kimball in a conference report. We prayed with him, fasted with him, laughed with him, shed tears with him. We studied with him, testified to him, thought about him. We loved him.

Halfway through a lesson on temples and temple marriage, he stopped us and asked us to be quiet a moment. He wanted to think. I thought how Italian that was, to ask for a minute to think, and I smiled. He took a deep breath and finally said, "Elders, I want to be baptized Sunday."

It was a beautiful ceremony -- the music by the sisters was perfect, and the testimonies borne were touching. Pasqaule came up out of the water and smiled a warm, innocent smile. I thought of our old fruit vendor. Perhaps someday I'd learn to smile as they did. Elder Lewis, Pasquale, and I embraced each other. His life had changed. And so had ours.

When I was transferred a week later, I was sad yet elated. I had been with Elder Lewis only a month, and it had passed all too quickly; we would have liked to work together five. Our initial conflict had been painful, yet it was the catalyst that had changed our missions. I had learned to love a country and a people; he had learned to be more effective in sharing his love. Together, we had found a great joy in sharing what we loved so much - - the gospel -- with a people that we loved with all our hearts.

As we ambled through the foggy cobblestone streets of Florence that night on the way home from Pasquale's apartment, I felt a lump in my throat. "Can you believe the progress Pasquale's made? He'll be a bishop some day," I said.

"Stake president," Elder Lewis replied matter-of-factly.

"First we have to baptize a stake, though."

We spontaneously quickened our pace, and finally broke into a jog as we made our way home through the fog-filled streets to Via Boito.

Mitchell Lee Edwards, an English major at Brigham Young University, is elders quorum instructor in his BYU ward.

© 2004 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

The Microfilm Mission of Archibald F. Bennett

By Kahlile Mehr

Kahlile Mehr, "The Microfilm Mission of Archibald F. Bennett," Ensign, Apr. 1982, 69

Soon after becoming secretary of the Genealogical Society of Utah in 1928, Archibald F. Bennett came across a statement made in 1911 by Nephi Anderson, assistant secretary:

"I see the records of the dead and their histories gathered from every nation under heaven to one great central library in Zion—the largest and best equipped for its particular work in the world."

Brother Bennett did not conceive at that time how this might be accomplished; a full decade would pass, in fact, before the technology of microfilm would become available as a means to fulfill Anderson's prediction. But in time, Brother Bennett would become the main impetus behind a microfilming program that would reach to all nations of the world.

Hints that microfilm would be the recording tool of the future began trickling in. "I would watch this. Something may come of it." The note, sent from Elder John A. Widtsoe to Archibald Bennett in the early 1930s, accompanied an issue of Popular Mechanics magazine with an article marked describing a new microfilm camera. At about the same time, Ernst Koehler, a German researcher and photography enthusiast, proposed to the General Board of the Society that microfilm be used to copy the records of his native Germany. He also sent a proposal to the highest record officials in Berlin, but no response was received. In 1936, Germany undertook a massive program of its own to film and preserve many of its parish registers.

In late 1937 and early 1938, James Kirkham, a Society Board member, toured Europe in an official capacity to evaluate and set in order the genealogical activities of the missions. He visited archives throughout the continent—and witnessed the German filming program firsthand.

It was time to take advantage of the new technology. A letter dated 12 May 1938 and signed by Archibald Bennett was sent to stake genealogical representatives; it described the potential of microfilm "to obtain copies of inaccessible books in distant libraries; old, rare and dilapidated books and manuscripts which are disintegrating through age or handling; and copies of original, unprinted records such as parish registers kept in the various countries of Europe." Funds were required for such an undertaking, and Brother Bennett encouraged the representatives to secure Society membership dues and donations amounting to no less than ten dollars per ward. The response was heartening but not sufficient. The problem of funding would not be resolved for several years to come.

The Society purchased an Argus microfilm reader in time to demonstrate its use to October conference visitors. In November a camera and processor were purchased, and intensive filming began late in 1938. The initial filming projects were nineteenth century records from the Salt Lake, Manti, and Logan temples.

Filming was not a complicated procedure in those early days. As Brother Bennett recorded on January 5, 1939, "Decided to begin immediately the photographing of the Manti Temple Records. Left at 2:25 P.M. with Bro. Kirby in his car, accompanied by Brother Koehler, the photographer, and his 17 year old son Willie, and with all the equipment in suitcases and boxes. ... Arrived about 7 P.M. ... Brother Koehler installed his machine in the record vault." A few people, a camera, and a car—that is how it was in the beginning.

World War II temporarily slowed filming ventures, but also served to reinforce Brother Bennett's argument that microfilming was a good answer to the problem of preserving record content from loss in an uncertain world. The war also increased the demand for microfilm technology, thus spurring the improvement and availability of microfilm equipment and supplies. And in 1944 the Society began to receive direct funding from the Church —a development that would move the microfilming effort ahead significantly.

Brother Bennett and Ernst Koehler were commissioned to go east in 1946 for the purpose of negotiating new filming projects. The two were granted permission to microfilm a collection of parish registers at the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Mt. Airy in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. While Brother Koehler filmed at Mt. Airy, Brother Bennett began an exhaustive schedule of visits to historical societies, archives, and libraries in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Vermont in the northeast; and Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia in the south. He explained the Society's offer to film and provide them a positive copy for the privilege. Very few could refuse such an offer. After the first week of successful negotiations he commented in a letter home, "It seems just like walking through a big orchard with plentiful fruit on every hand, and being able to pick what you want at will."

Success, however, was not guaranteed. Some record keepers were simply uninterested. But Brother Bennett would not accept a negative response. His first test came in Maryland; at Annapolis, the state archivist explained that all their records had been filmed during the war and three positive copies printed. Their plan was to send a positive copy to the Huntington Library in California, one to the Public Record Office in London, and the last print and its negative to the Library of Congress. He was satisfied with the arrangement and saw no need for further filming.

Brother Bennett tried several lines of persuasion without success. Could the Society obtain a copy? No. Could the Society make an exchange for records of surrounding states? No. Brother Bennett began to wonder if he had reached an impasse.

Finally, he presented a letter which granted permission to film the records of New Jersey and explained the work in Pennsylvania where they intended to film in the counties. To his surprise, the archivist began to show interest. It seemed that there were still records in Maryland's counties that had not yet been gathered to the state's hall of records. If the Society could film those, perhaps something could be done about getting prints of the previously produced films. The archivist kept Brother Bennett past closing time to work out the details. In commenting on the incident, Brother Bennett later wrote, "It is one of the most important [missions] I have ever performed—pleading our case before these important officials ... and to witness how their hearts are softened, even after they know I am a Mormon and our program sponsored by a Church."

A week later Brother Bennett was in Connecticut at the state library. The hurdle here was much tougher than in Maryland. Two previous written applications to film at the library had been refused. Upon Brother Bennett's arrival, the state librarian asked if this was not the same request that had been made twice before. Brother Bennett said yes. "Well, you are quite insistent, aren't you?" came the response. Brother Bennett answered that he was, then continued: "Thousands of our people, including three Presidents of our Church, have ancestors born in Connecticut. I myself have fifteen or twenty. We shudder to think what would happen to these records if an atom bomb were dropped over the State Library." Brother Bennett's persistence paid off, and permission was granted.

It must have seemed strange to the proprietors of these eastern archives for a westerner to appear and make such an outlandish offer—to film their records, and at no cost to them! But Brother Bennett was able to convince them that he was serious. He wrote: "Ever present with me is the realization of all the families whose ancestral records are contained in these choice collections. I believe they are pulling for us in our efforts in their behalf." In just over a month, Brother Bennett had obtained permission to film in the central archives of seven states as well as in many county offices of Pennsylvania.

With the projects in the eastern United States barely under way, Archibald Bennett found himself looking even further east—this time to Europe. Pre-war contacts had been made with record keepers in England, Denmark, Germany, and Italy; then World War II had intervened. In 1945 the agent in Denmark, Arthur Hasso, had renewed contact with the Society and in 1946 received a contract to begin filming. The next year Brother Bennett was chosen to represent the Society in Europe to develop prospects for filming. His success would be overwhelming, though not without difficulty.

He arrived at Plymouth, England, in June, and for the next four months traveled in Wales, Scotland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Holland, France, Belgium, Switzerland, and Italy. If his proposals seemed extraordinary in the United States, one might imagine what response a record keeper in a foreign country would have to this stranger from an unknown society in an obscure state on the other side of the world!

A major problem encountered in some countries of Europe was opposition due to disagreement with the Latter-day Saint doctrine of baptism for the dead. This was crucial because most of the valuable genealogical records were of religious origin and controlled by ecclesiastical authorities. Early prospects in England were dimmed when the Archbishop of Canterbury refused permission for the Society to film English parish registers; one of his reasons was the Mormon belief in baptism for the dead.

In Wales and Scotland, ecclesiastical authorities did not intervene; and, conveniently for the Society, many parish records had already been gathered to central civil repositories. The major objective in the British Isles thus became to get projects under way in these locations.

Brother Bennett and James Cunningham, genealogical supervisor of the British Mission, arrived in Aberstwyth, location of the National Library of Wales, on 22 June for an appointment with Sir William Davies, the national librarian. They were to make a formal request to begin a five-year project—certainly one of the largest microfilming efforts ever to be undertaken in Britain.

Davies was gracious and sympathetic to their request. He even offered to let them use a camera already on order and due to arrive at the library soon. In addition, he offered to be their advocate with officials, both civil and religious, from whom final sanction would be required.

The reception they received three days later in Edinburgh was hardly so cordial. As in Connecticut, early proposals for filming had been refused; even so, Brother Bennett was undaunted. The archivist welcomed them but balked when the proposal to film was renewed; opposition had apparently increased and permission would not be granted.

Brother Bennett suggested one final alternative: Could the filming proceed, if for no other reason than simply to preserve the record content from destruction? The archivist reconsidered; he would at least resubmit the proposal. The answer did not come for five years; but when it came, the cablegram from the British Mission office read, "Rejoice with me! We have received permission to microfilm all the church registers and early census records of Scotland."

From England, Brother Bennett traveled in the company of Alma Sonne, European Mission president, to Stockholm. At a gathering of LDS mission presidents from across Europe, Brother Bennett impressed upon them his own deep feeling for the immediacy of the work: "I told them I, too, was speaking in behalf of a mission field—more extensive and including more people than all the other missions combined. Despite the fact that it was under the Presidency of the Prophet Joseph Smith and was blessed with labors of numbers of the greatest missionaries for 117 years, not a single baptism had been performed in that mission. They had made converts, perhaps millions of them, but no baptisms [meaning that ordinance cannot be performed in the spirit world; it must be done on earth by proxy]. For their mission to succeed, the records to identify those in the spirit must be gathered from the nations and sent to the temples."

The success in Wales and hopes for Scotland were but a prelude to events following in quick succession. In Denmark, Brother Bennett reviewed the excellent progress being made by Arthur Hasso. A tentative agreement was concluded in Sweden and a contract finalized in Norway.

In the first two months of his European mission, Brother Bennett had negotiated for decades of filming contracts; during the final month and a half he finalized agreements for filming in Holland and the Vaudois parishes of Italy, and negotiated tentative approval for France and Switzerland. His sole disappointment was Germany, where military restrictions made negotiations impossible.

The European venture of 1947 was followed by a second trip in 1948 to conclude undone business of the previous year. Finland, Belgium, and Germany were added to the list of countries in which filming would be done. Success was virtually unlimited.

The 1948 trip also presented Brother Bennett an opportunity to personally participate in one of the filming projects in the villages of the Vaudois in northern Italy. Brother Bennett, along with James Black, microfilmer, and James Barker, French Mission president and his wife, Olive, traveled by car to the remote mountain seclusion of the Vaudois parishes. They soon discovered that the power supply was insufficient to operate their camera except at the central village of Torre Pellice. They set up the operation in a hotel room, converting the clothes closet into a darkroom. Thus began a three-week effort during which 1,476 volumes of parish registers were filmed.

Brother Bennett and the Barkers would travel in the car along narrow dirt roads and cart trails to outlying parishes and bring the records into the hotel where Brother Black would film them. On one occasion the road ended about a twenty-minute walk from the village where the records were located. Brother Bennett ascended the hillside in a pouring rain, bundled seventy-eight registers in Brother Black's raincoat, and returned down the slope.

Just before leaving Europe in October 1948, Brothers Bennett and Black witnessed the beginning of the Swedish microfilming effort in the Stockholm City Archives. At that moment filming was in progress in Norway, Denmark, Finland, East Germany, Holland, Switzerland, England, and Wales.

After the 1948 tour, Archibald Bennett withdrew from the microfilming program and returned to his teaching, writing, and other efforts to promote genealogical work throughout the Church. Responsibility for the filming work was delegated to the superintendent of the Society, L. Garrett Myers.

While Brother Bennett no longer actively negotiated for records, he promoted the program in a different way. In 1952 he presented a paper to the Society of American Archivists describing the history of the Genealogical Society's worldwide filming effort. Later published in The American Archivist, it was the first major publicity given the program through professional channels. The article was followed in 1959 by a shorter one in Archivum, an international archival journal. The effect of this article was substantial. Upon reading it, the archivist of Poland wrote requesting assistance with filming church records in their archives. The filming was initiated in 1968, a few years after Brother Bennett had passed away.

Those who visit the Genealogical Society Library today may never hear or see the name of Archibald F. Bennett; indeed, the library little resembles the small, unnoticed collection that he inherited as Society secretary in 1929. But its film holdings have now passed the million mark and filming operations continue in all parts of the world, reflecting the vision of a man committed to building the Kingdom on both sides of the veil.

© 2004 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

Early Missionary Work in Italy and Switzerland

By James R. Christianson

James R. Christianson, "Early Missionary Work in Italy and Switzerland," Ensign, Aug. 1982, 35

In October 1849, nearly two years after the Saints' arrival in the Salt Lake Valley, missionaries were called to take the gospel to Italy, Denmark, Sweden and France, and to continue the work in England. Lorenzo Snow, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve of less than a year, traveled with others to England on his way to the Continent. Then accompanied by Joseph Toronto, a Utahn of Sicilian ancestry, and Thomas B. H. Stenhouse, a recent British convert, he traveled on to Italy, arriving on 23 June 1850.

They found success among a Protestant group known as the Waldenses, who lived in the Piedmont region of Italy. Elder Snow wrote and published The Voice of Joseph, a missionary tract which circulated widely throughout northern Italy. He also directed the translation of the Book of Mormon into Italian.

Having received a commission to introduce the gospel into other nations if circumstances permitted, he set apart Elder Stenhouse in November 1850 as president of the Swiss Mission and sent him on his way over the Alps to Switzerland. Following is a photographic outline of places, people, and some events that were significant in establishing the gospel in Italy and Switzerland.

Elder Lorenzo Snow, who introduced the restored gospel in Italy. He left his family in humble circumstances in Salt Lake City. "Did the people of Italy but know the heart-rending sacrifices we have made for their sakes," he wrote, "they could have no heart to persecute."

[photos] Photography by James R. Christianson

[photo] After arriving in Italy, Elder Snow was impressed to begin laboring among the Waldenses, a Protestant group located at the base of the Alps in the Luzerne Valley. He concentrated his efforts in La Tour, presently the city of Torre Pellice. The people there were remnants of a religious sect founded in France in the twelfth century by Peter Waldo. Driven by persecution, they had sought refuge in northern Italy. Their isolated location enabled them to retain their religious traditions and preserve several dialects of their native tongue.

Impressed with the prospect of success among these people, Elder Snow wrote soon after his arrival: "With a heart full of gratitude, I find an opening is presented in the valleys of Piedmont, when all other parts of Italy are closed against our efforts. I believe that the Lord has there hidden up a people amid the Alpine mountains, and it is the voice of the Spirit that I shall commence something of importance."

[photo] During the months he was in La Tour, Elder Snow and his companions often climbed Mt. Castelluzzo, which he named "Mt. Brigham," to visit the Waldensen families. He loved its natural beauty: "The clouds often enwrap these mighty eminences," he wrote, "and hide their frowning grandeurs from our view. At other times they are covered with snow, while at their feet the vine and fig tree are ripening their fruit."

It was to this mountain that Elder Snow went to plead for the life of a three-year-old boy who was near death. Reflecting on the urgency of their work, which, as yet, was moving slowly, Elder Snow regarded the healing of the child as a circumstance "of vast importance. I know not of any sacrifice which I can possibly make, that I am not willing to offer, that the Lord might grant our requests." Upon returning from the mountain, he administered to the child, who, by the next day, was completely healed.

[photo] Old homes of the Waldenses, high on the mountainside. Active missionary labors continued among these people from September 1850 until 1853, when the missionaries left to proselyte in other areas.

The harvest among the Waldenses for which they worked and prayed didn't materialize on the scale they had hoped. Weighted down by religious tradition, few who heard the message—either Protestant or Catholic—were equal to the challenges faced by those who dared break with the past. However, of the 211 Italians who joined the Church during those first years of missionary work in Italy, most of the converts were Waldenses. Most who remained faithful emigrated to America.

[photo] A Waldensian home on Mt. Castelluzzo. The missionaries were heartsick to see the poverty among the people. A crop failure contributed to their already desperate plight. And the hardships of the people worked a hardship on the elders. "Think not," Elder Snow wrote in a letter, "that we are amid the marble palaces, nor surrounded by the choice productions of art which adorn many portions of this wonderous land. Here, a man must preach from house to house, and from hovel to hovel. Here, many a dwelling has no glass in the windows, and from the scarcity of fuel there is often no fire upon the hearth; and during the long winter evenings, the family are huddled together in the stable among the cattle, for the sake of a little warmth which they cannot find elsewhere."

[photo] High on Mt. Castelluzzo is an overhanging rock accessible only through a narrow passageway. On 19 September 1852, Elder Snow and his three missionary companions (Elder Jabez Woodard of London had joined them) climbed to the secluded spot, sang praises, offered prayers, officially organized the Church in Italy, and prophesied concerning the latter-day work. From then on, the mountain was known among members of the Church as "Mt. Brigham," and the rock as "The Rock of Prophecy."

Two months later, on 24 November 1850, the four elders again climbed to the "Rock of Prophecy"—to carry out additional important ordinations for the furthering of the work. Since Elder Snow felt he should leave Italy soon to take the gospel to other areas of the Continent, he ordained Elder Woodard a high priest and set him apart as presiding officer of the Church in Italy. He also ordained Elder Stenhouse a high priest and commissioned him to begin missionary work in Switzerland.

[photo] The Alps, over which Elder Stenhouse journeyed on his way to Geneva, Switzerland, in December 1850. Two months later, Elder Snow made a similar journey to work with Elder Stenhouse for a month. Trunk in hand, he crossed the mountain passes in the middle of a severe snowstorm, "scarcely knowing," he said, "whether I was dead or alive. It is one thing to read of traveling over the backbone of Europe in the depth of winter, but doing it is quite different."

[photo] Geneva, Switzerland—called by Elder Stenhouse "the Protestant Rome." This is where John Calvin and other early reformers did much of their work. When Elder Snow visited Geneva and dedicated Switzerland two months after Elder Stenhouse had arrived, he was greeted by a handful of interested persons who became the nucleus of two small branches numbering twenty persons by the time he returned a year later.

With the arrival of three additional elders, the work spread throughout the Protestant cantons (states). At a conference held in Geneva on 25 December 1853, it was reported that 186 persons had been baptized and that branches were functioning in Canton Zurich and Canton Baselland. (Photography by R. Gordon, courtesy of Globe Photos.)

[photo] The street in Geneva where Elder Stenhouse lived, 1851.

[illustration] The first person taught the gospel in Switzerland was a shoemaker. Here he receives the gospel from Elder Stenhouse.

[photo] The Ruben family, the first to join the Church in Switzerland. Significant among the early converts were a retired minister who served as translator, Elder Stenhouse's landlord, a shoemaker, a newspaper publisher, a hospital administrator, and a member of the Swiss aristocracy. These people proved vital to a successful beginning for the Church in their land. As the need arose, their leadership, linguistic abilities, and financial resources were made available—and the work continued to progress.

[photo] The Ballif home in Lausanne, Switzerland. Missionaries moved into the third floor of this home, being spared much hardship by the kindness of the Ballifs.

[illustration] Lausanne, Switzerland, where Elder Stenhouse met and baptized Serge Louis Ballif, an ancestor to President Ezra Taft Benson.

[photos] Serge Louis Ballif and his wife, Elise. A wealthy man, Brother Ballif gave of his money freely to support the missionaries and publish tracts and newsletters. He served as a local missionary, baptized several families, and then emigrated to America. He later returned to Switzerland as a missionary in 1860, and as mission president from 1879 to 1881. His son, Serge Frederick, served as president of the Swiss and German Mission from 1905 to 1909, and from 1921 to 1923.

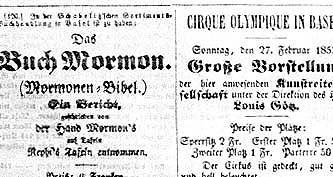

Book of Mormon advertisement that preceded the elders to the city of Basel, in the German-speaking area of Switzerland. It was placed by a book dealer who thought the book might sell.

[photo] First missionaries in German-speaking Switzerland: Georg Meyer and Jacob Secrist. Until they arrived, missionaries had spoken French.

[photo] William Budge, one of the earliest missionaries in Switzerland. A Scot, he was arrested and imprisoned repeatedly for preaching, and was finally expelled from the country. After leaving Switzerland, he went to Dresden, Germany, where he taught Karl G. Maeser.

[photo] Mission office in Bern, Switzerland, 1869.

[photo] In 1869, with Karl G. Maeser as mission president, Church headquarters in Switzerland were moved to the city of Bern. (Photography courtesy of Three Lions.)

[photo] Many of the early Swiss converts came from the Alpen Highlands. They were mostly rural people. As the proselyting of the elders and members became increasingly successful (20 baptisms in 1851, 50 in 1852, and 116 in 1853), the attention of the clergy and the press was drawn to the Church. Local press coverage of Latter-day Saint history and doctrine caused opposition to intensify. Throughout the 1860s, official restrictions and violence against foreign elders placed the burden of effective preaching in the hands of local missionaries. A courageous response by native members continued the Church's momentum, however. But disaffections were also common, due to the negative press, fines, imprisonment, banishment, and physical abuse members and missionaries sometimes received.

But in 1864, the Swiss government declared that the Latter-day Saints were to be recognized as a Christian sect, giving the Church official religious freedom and right of assembly. Later the Federal Council of Switzerland stated that Latter-day Saints had as much right to the protection of the federal constitution as the adherents of any other faith.

The Swiss people gradually increased their tolerance towards the Church, possibly because of their traditional reverence for individual freedom—and their boredom with the anti-Mormon rhetoric pouring from the press and pulpit. By 1875, several organized groups of Church members were found in the Protestant cantons (states). By the 1880s and through the turn of the century, baptisms and the number of foreign elders in the country were at high levels and the Church continued to grow at a steady rate. After fifty years of proselyting, there were over one thousand faithful members in Switzerland. In addition, 2,060 had emigrated to America. (Photography by Peter Van Dyck, courtesy of Photounique.)

[photo] Karl G. Maeser walked many miles to this home in Zwischenflu, Switzerland, where he taught and converted members of the Kunz family in 1868.

[photo] John Kunz, Jr., who upon first contact refused the gospel. Years later, he declared: "It took a Karl Maeser to teach me the truth." Brother Kunz emigrated to America, returned to Switzerland as a missionary, and raised a large family in Idaho, typifying the early European convert to the Church.

Excerpts from Brother Kunz' journal reveal much concerning the character of the Church and the nature of missionary work in rural Switzerland in the late nineteenth century:

"febr. 9, 1885, Wrote Home and after Dinner started to visit Sister Spory it Commence to rain and Snow terribly Visited Gottlief Eshler, Brother of Arnold in Montpelier, he is in Weisenburg he looks to be a honest Chap. We had quiet a chat together, went on further got to a stable and prayed to the Lord to bless me on my stormy Journey and felt like asking him for shelter, which I soon found in the house of Brother Sporys father-inlaw ... sister Spory had Called me into the house and she with her Mother comenced on me about Temple building claiming it was for some unholy secret purpose of the Priesthood, I had plenty to do, for I soon found I had it up with a well posted and educated lady but I defended the Cause of Zion as best possible and Came out Victor. I soon had a nice Meal before me and was treated fine.

"Aug 9 ... I walked to Gumligen and took train to Longman and then walked to Brother Eglia in Eisekachen after dinner the saints came and we had a good turnout for a meeting and although no strangers there had quite some hard work with Brother and Sister Beutler whom I was endeavoring to Show the nessessity to Emigrate but failed in my attempt for they concluded not to go as they were to much in Debt.

"I stayed over night but to my disappointment for the fleas where in my Bed by the hundreths but it got Morning. Aug 10. after walking a ways I went into Tnulee and stripped naked and declared a war for the fleas and so it was for it took me hours to clean myself.

"Aug. 12. I walked to Kapf by Reidenback and was badly wanted for there was some Relatives on a visit, that wished to hear Mormonism explained which however I did and was feeling first rate. got a splendid Bed and Rest."

Gospel topics: Church growth, Church history, missionary work

© 2004 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

News of the Church:

Triple Combination Published in Italian

"News of the Church: Triple Combination Published in Italian," Ensign, Jan. 1983, 79

For the first time, thousands of Latter-day Saints who speak and read Italian can obtain the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price in one volume. The new Italian triple combination was published in September 1982.

In previous years, these three latter-day scriptures have been available in Italian under separate covers. According to Poul Stolp, area materials management manager for the Church in Europe, the text of the Book of Mormon is the fourth edition in Italian (1982). The text of the Doctrine and Covenants and the Pearl of Great Price is the second edition in Italian (1981).

Although not exactly the same as the 1981 English triple combination (it retains the former index, footnotes, and chapter headings), the Italian three-in-one does contain sections 137 and 138 of the Doctrine and Covenants and also Official Declarations 1 and 2, Brother Stolp explained. It also includes, in Italian, the latest version of the Articles of Faith in the Pearl of Great Price. The newly published volume was printed in Frankfurt, Germany, the center for printing Church materials for Europe.

A major figure in the work resulting in the Italian triple combination is Pietro Currarini, Italian translation supervisor in Livorno, Brother Stolp said. After completing most of the work on each of the three scriptures, Brother Currarini submitted his revision to other staff members for review. The work was mostly one of revision, not retranslation.

Approximately 3,000 copies of the Italian triple combination have been printed and are available at the Church distribution center in Milano, Italy. Cost is 20,000 Italian lire. Members and nonmembers in other areas can obtain copies by ordering them through local distribution centers. Those living in the United States and Canada can obtain copies through the Salt Lake Distribution Center, 1999 West 1700 South, Salt Lake City, Utah 84104 ($20 per copy; stock no. PBMI4041IT).

© 2004 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

News of the Church:

BYU Professor Tracing Path of Book of Abraham Papyri

"News of the Church: BYU Professor Tracing Path of Book of Abraham Papyri" Ensign, June 1985, 75

Between 1818 and 1821, a group of mummies was taken from an Egyptian tomb into the light of day for the first time in centuries.

In mid-1835, the Church bought four of those mummies, along with two or more rolls of papyri. The Prophet Joseph Smith then obtained, through revelation, what we now have as the Book of Abraham in the Pearl of Great Price.

Those events—the unearthing of the mummies and their later purchase in Kirtland—are known to have occurred, but much of what happened in between has puzzled scholars for 150 years.

Many Church members, of course, have read how the mummies and papyri came from Egypt to Kirtland, Ohio. The story is recorded in Church history; it was told by Michael H. Chandler, the man from whom the mummies were purchased, and was written by Oliver Cowdery. But that story has been the subject of intense study. "The historical background of the Book of Abraham has always been obscure in the Church," says H. Donl Peterson, a professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University.

Bit by bit, however, facts have come to light to establish what happened after the mummies were removed from their long-darkened tomb. With the help of researchers in Italy, during the past year Dr. Peterson has discovered the will of the man who brought the mummies out of Egypt, along with other documents that shed light on the character of the man himself and record the journeying of the mummies and papyri.

Briefly, the story told to Oliver Cowdery by Michael Chandler relates that crews directed by Antonio Lebolo unearthed eleven mummies with accompanying writings in Egypt in 1831. Mr. Lebolo was traveling to Paris, but en route he put in at Trieste, where he became ill and died. It was said his will specified that the mummies and papyri be sent to his nephew, Michael Chandler, of Dublin, Ireland. From Dublin, they were sent on to New York City, where Mr. Chandler claimed them in the winter or spring of 1833. He exhibited them throughout the eastern United States. While in New York City, he was told by a stranger that Joseph Smith could translate ancient languages. Two years later Mr. Chandler took his exhibit to Kirtland, Ohio, where the mummies and papyri were shown to Joseph Smith.

The Prophet was asked to translate a few of the characters from the papyri. His translation agreed, so far as Mr. Chandler could determine, with translations offered by learned men in the East. Shortly, a sale was negotiated; with money from two major donors and subscription donations by the Saints, the Church bought the four mummies and the papyri.

One overriding certainty about the papyri is that it resulted in inspired scripture. But questions about how the papyri came to the United States and into the hands of Joseph Smith have remained unanswered since 1835. What, for example, was the real relationship between Antonio Lebolo, the Piedmontese gendarme sometimes referred to as a "celebrated French traveler," and Michael Chandler, an Irishman? Where is proof that the mummies were in truth willed to Mr. Chandler? Were the mummies actually sent from Trieste to Dublin, then on to New York City? Some of Mr. Lebolo's contemporaries in Egypt paint him as a villain; what kind of man was he really?

These are just "some of the questions we've never had any answers to," Brother Peterson says.

Some information was already available before Brother Peterson began his research. It was known that Antonio Lebolo, from the Piedmont area in what is now Italy, worked in excavations in Egypt in the late second and early third decade of the 1800s. He was employed by Bernardino Drovetti, another Piedmontese who was later French consul general in Egypt. Dr. Peterson's research has revealed that Drovetti had distinguished himself as a colonel under Napoleon and that Lebolo had served as a French officer in the gendarmarie in the Piedmont. (Legal documents show that Mr. Lebolo signed his first name in its French form—"Antoine"—during the Napoleonic occupation.) When Napoleon was deposed, it became politically necessary for Lebolo to leave the country.

In Egypt, Antonio Lebolo was the supervisor of tomb excavations in the Theban area for his friend Drovetti. "The digs were taking place in El Gournah, on the west bank of the Nile, across from the ancient city of Thebes, which is the present city of Luxor," Brother Peterson explains. The science of archaeology was then in its infancy at best, and it would be inaccurate to call the excavators archaeologists. They looted tombs of artifacts and mummies that went not only to some of the most prestigious museums in Europe, but also to private collections of the wealthy who exhibited their Egyptian curios for guests.

It was a "dirty business" that bred not only competition, Brother Peterson points out, but also thievery and, sometimes, violence. Antonio Lebolo was accused of both. It is important to note that his accusers have been labeled as equally guilty by other observers, and their accounts may be self-serving. From this distance in time, it may be impossible to learn the truth, Brother Peterson says. However, reports of one countryman, Count Carlo Vidua, indicate that Mr. Lebolo was a conscientious Drovetti employee who unearthed a number of Ptolemaic mummies (from the period of Greek influence in Egypt) on his own time. These were mummies from members of the priestly class, who took great care to preserve their important papyri documents. Lebolo hosted many European dignitaries amid the ruins of the Theban excavations.

While in Italy in 1984 to research Antonio Lebolo, Brother Peterson and his research assistant, Bruce H. Porter, enlisted the aid of Church members Adriano Comollo, a former BYU student who had also had some training in genealogical research; his wife Jerrilyn, originally from Arizona; and Patricia Pianea, an interpreter and translator. While Brother Peterson was researching in Egypt, Brother Comollo located the will of Antonio Lebolo in the papers of a notary named Buffa who served Mr. Lebolo beginning in 1810. The notary, equivalent to a family lawyer, had been serving the Lebolo family since the late 1700s.

Brother Peterson returned to Italy to join in the search and photograph the documents. The Comollos continued the effort after the BYU professor returned to Utah. They discovered documents that fill in many of the blanks about Antonio Lebolo's life from his first marriage in 1797 until his death in 1830.

The documents indicate, for example, that Lebolo returned to his home in Castellamonte sometime in 1825 or 1826. Lebolo's first wife had died in 1821 in Castellamonte while Lebolo was exiled in Egypt. His second wife was from Africa—a black woman who had been a slave. Antonio Lebolo had seen that she received a Christian education and married her in June 1824. She had two small daughters, and one of them apparently became gravely ill for a time in Trieste during their return trip to Italy. She had been given some last rites by a priest—hence, perhaps, the story that Antonio Lebolo had himself died in Trieste, Brother Peterson suggests. Three sons were born to Antonio and his African wife, Anna Marie.

The papers of the notary show that Antonio Lebolo was a respected man in Castellamonte, "very well-to-do" at the time of his death on 19 February 1830, but he was not a very good manager, Brother Peterson says. His will disposed of assets valued at 30,000 lira, but much of that was in uncollectible debts. There was no mention of any mummies.

An 1831 document pertaining to the Lebolo family, however, makes it clear that Pietro, Antonio's oldest son by his first wife, Marie, traveled to Trieste to obtain money on behalf of the family for eleven mummies that had been entrusted to one Albano Oblassa. Pietro was also authorized to obtain payment for a menagerie of exotic animals his father had sold to a couple. Lebolo had kept ostriches while living in Trieste, and since ostrich feathers were highly prized for fashionable dress, these may have been ostriches.

Documents show that the mummies were subsequently sent from Trieste to New York. Dublin, Ireland, is not mentioned in the document. An Italian man in Philadelphia was commissioned to serve as an agent for the Lebolo family to sell the mummies in the United States. Among the Lebolo papers, there are letters inquiring about the money that was to have come from the sale.

"How Michael Chandler fits in is still a mystery," Brother Peterson comments. His connection with the Lebolo family, if any, and how he came into possession of the Egyptian artifacts have yet to be established. But Brother Peterson says he has discovered sixty-one Philadelphia newspaper advertisements for the Chandler exhibit.

Michael Chandler sold the mummies over a two-year period. Two or more went to the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, where they were used as cadavers for medical students. By the time he arrived in Kirtland, Ohio, he had only four left. Joseph Coe (later a troublesome apostate) and Simeon Andrews each contributed $800 toward the $2,400 purchase price for Mr. Chandler's Egyptian items; member donations made up the rest. The mummies and the papyri were presented to the Prophet Joseph Smith.

Documents show, Brother Peterson adds, that Mr. Chandler had been pursued for several years by lawsuits, probably as a result of the Egyptian artifacts, including one suit filed in Geauga county, where Kirtland is located. Evidently the suits were unsuccessful. For $600—just one quarter of the money he got for the mummies and papyri—Mr. Chandler bought a fine Parkman, Ohio, farm, settled into the life of a farmer, and raised a family of twelve children. He died in October 1866.

© 2004 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.